Using Dietary Supplements Wisely

What’s the Bottom Line?

How much do we know about dietary supplements?

The amount of scientific evidence we have on dietary supplements varies widely—we have a lot of information on some and very little on others.

What do we know about the effectiveness of dietary supplements?

- Studies have found that some dietary supplements may have some benefit, such as melatonin for jet lag, and others may have little or no benefit, such as ginkgo for dementia.

- Supplements you buy from stores or online may differ in important ways from products tested in studies.

- Most research shows that taking multivitamins doesn’t result in living longer, slowing cognitive decline, or lowering the chance of getting cancer, heart disease, or diabetes.

What do we know about the safety of dietary supplements?

- Taking a multivitamin is unlikely to pose any health risks.

- Dietary supplements may interact with your medications or pose risks if you have certain medical problems or are going to have surgery.

- Many dietary supplements haven’t been tested in pregnant women, nursing mothers, or children.

- Some products marketed as dietary supplements—promoted mainly for weight loss, sexual enhancement, and bodybuilding—may contain prescription drugs not allowed in dietary supplements or other ingredients not listed on the label. Some of these ingredients may be unsafe.

What Are Dietary Supplements?

Federal law defines dietary supplements as products that:

- You take by mouth (such as a tablet, capsule, powder, or liquid)

- Are made to supplement the diet

- Have one or more dietary ingredients, including vitamins, minerals, herbs or other botanicals, amino acids, enzymes, tissues from organs or glands, or extracts of these

- Are labeled as being dietary supplements.

What Are Herbal Supplements?

Herbal supplements are a type of dietary supplement containing one or more herbs. They are:

- Sometimes called botanicals

- Made from plants, algae, fungi, or a combination of these

- Sold as teas, extracts, tablets, capsules, powders, or in other forms.

Dietary Supplement Use in the United States

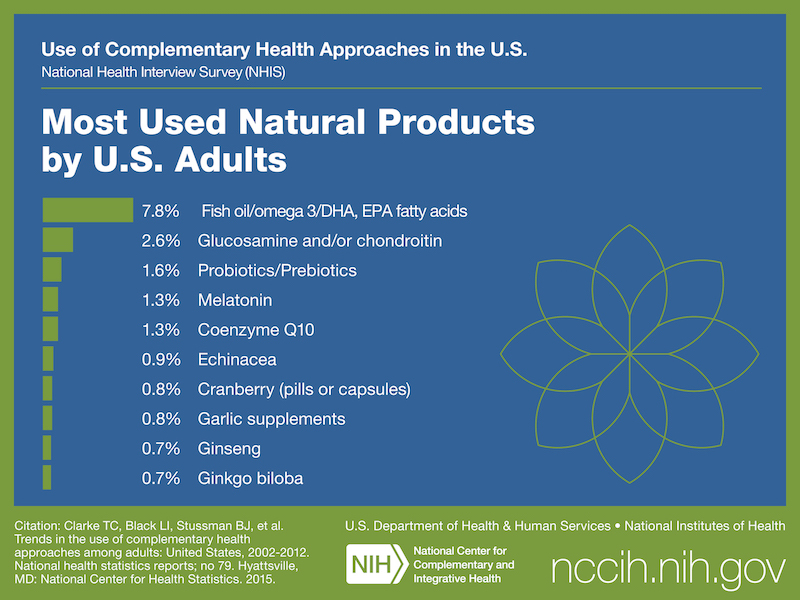

According to the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, which included questions on Americans’ use of natural products (dietary supplements other than vitamins and minerals), almost 18 percent of adults and about 5 percent of children used these products in 2012.

More

- The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey collected data from 2011 to 2012 on the use of all types of dietary supplements. It found that 52 percent of American adults took at least one dietary supplement. Multivitamin or multimineral supplements—a product having 10 or more vitamins or minerals—were one of the most common, and 31 percent of all adults took them. This was a decrease from 1999 to 2000, when 37 percent of American adults reported using multivitamin or multimineral supplements. Women were more likely than men to take dietary supplements.

- For more information on dietary supplement use in the United States, including among children, see the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) webpage with statistics about complementary and integrative health approaches.

Why Do People Use Dietary Supplements?

American adults often use dietary supplements for wellness. According to the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, 89 percent of American adults who took dietary supplements other than vitamins and minerals gave wellness-related reasons for using them, including:

- General wellness or disease prevention (83 percent)

- Improve immune function (42 percent)

- Improve energy (31 percent)

- Focuses on the whole person—mind, body, and spirit (27 percent)

- Improve memory or concentration (22 percent).

Federal Regulation of Dietary Supplements

- Federal regulations state that companies are responsible for having evidence that their dietary supplements are safe and for ensuring that product labels are truthful and not misleading. Manufacturers are required to produce dietary supplements in a quality manner, ensure that they don’t contain contaminants or impurities, and label them accurately.

- However, rules for manufacturing and distributing dietary supplements are less strict than those for prescription or over-the-counter drugs.

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which regulates dietary supplements, requires that companies submit safety data about any new ingredient not sold in the United States in a dietary supplement before 1994. In all other cases, the FDA is not authorized to review dietary supplements for safety and effectiveness before they are marketed.

- The FDA can take action against adulterated or misbranded dietary supplements only after the product is on the market. In contrast, companies must show the FDA evidence that their prescription and over-the-counter drugs are safe and effective before the drugs are marketed.

- Once a dietary supplement is on the market, the FDA tracks side effects reported by consumers, supplement companies, and others. You can report any safety concerns you may have about a dietary supplement through the U.S. Health and Human Services Safety Reporting Portal.

- If the FDA finds a product to be unsafe, it can take legal action against the manufacturer or distributor, and may issue a warning or require that the product be removed from the marketplace. However, the FDA says it can’t test all products marketed as dietary supplements that may have potentially harmful hidden ingredients. In 2023, the FDA launched the Dietary Supplement Ingredient Directory, a webpage where the public can look up ingredients used in products marketed as dietary supplements and find what the FDA has said about that ingredient, as well as whether the agency has taken any action with regard to the ingredient.

- For more information on contaminants in dietary supplements, see the FDA’s Dietary Supplement Products & Ingredients webpage.

Health and Structure/Function Claims

- The labels on dietary supplements cannot claim that the product can diagnose, treat, cure, mitigate, or prevent any disease; claims like these are only permitted for drugs. However, some types of claims related to health or the way that the product affects the structure or function of the body may appear on dietary supplement labels.

- Health claims describe a relationship between a substance in the supplement and reduced risk of a disease or condition. They must be based on scientific evidence. For example, if a supplement label says “Calcium may reduce the risk of the bone disease osteoporosis,” that’s a health claim.

- Structure/function claims describe the effect of a substance on maintaining the body’s normal structure or function. For example, if a supplement label says “Calcium builds strong bones,” that’s a structure/function claim. Structure/function claims on dietary supplement labels must be accompanied by this disclaimer: “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, mitigate, or prevent any disease.”

- Advertising

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which regulates advertising, requires that advertising be truthful and not misleading.

What the Science Says About the Effectiveness of Dietary Supplements

- Some dietary supplements can be good for your health, while others haven’t been proven to work. For information on the effectiveness of different supplements, see the NCCIH webpage about dietary supplements.

- Studies of some supplements haven’t supported claims made about them. For example, in several studies, echinacea didn’t help cure colds and Ginkgo biloba wasn’t useful for dementia. Many times the research on a dietary supplement is conflicting, such as whether the supplements glucosamine and chondroitin improve symptoms of osteoarthritis.

- Strong evidence to back up claims made for dietary supplements is often lacking. For example, a 2022 review identified 27 ingredients frequently included in supplements with claims related to immune function, such as “supports healthy immune system” or “natural immune booster.” The reviewers searched the scientific literature for rigorous studies in people on the effectiveness of each ingredient, and they found evidence of this type for only eight of them. Some of the studies suggested possible benefits, but the evidence wasn’t strong enough to allow definite conclusions to be reached. Additional research is needed so consumers will know whether a dietary supplement promoted for immune health can help protect them from getting sick.

What the Science Says About the Safety and Side Effects of Dietary Supplements

- What’s on the label may not be what’s in the product. For example, the FDA has found prescription drugs, including anticoagulants (e.g., warfarin), anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin), and others, in products being sold as dietary supplements. You can see a list of some of those products on the FDA’s Health Fraud Product Database webpage.

- A 2012 Government study of 127 dietary supplements marketed for weight loss or to support the immune system found that 20 percent made illegal claims.

- Some dietary supplements may harm you if you have a particular medical condition or risk factor or are taking certain prescription or over-the-counter medications. For example, the herbal supplement St. John’s wort makes many medications less effective.

- Dietary supplements result in an estimated 23,000 emergency room visits every year in the United States, according to a 2015 study. Many of the patients are young adults having heart problems from weight-loss or energy products and older adults having swallowing problems from taking large vitamin pills.

- Although it’s still rare, more cases are being reported of acute (sudden) liver damage in people taking dietary supplements in the United States and elsewhere. The liver injury can be severe, can require an emergency liver transplant, and is sometimes fatal.

- Many dietary supplements (and some prescription drugs) come from natural sources, but “natural” does not always mean “safe.” For example, the kava plant is a member of the pepper family but taking kava supplements can cause liver disease.

- A manufacturer’s use of the term “standardized” (or “verified” or “certified”) does not necessarily guarantee product quality or consistency.

Safety Considerations

- If you’re going to have surgery, be aware that certain dietary supplements may increase the risk of bleeding or affect your response to anesthesia. Talk to your health care providers as far in advance of the operation as possible and tell them about all dietary supplements that you're taking.

- If you’re pregnant, nursing a baby, trying to get pregnant, or considering giving a child a dietary supplement, consider that many dietary supplements have not been tested in pregnant women, nursing mothers, or children.

- If you’re taking a dietary supplement, follow the instructions on the label. If you have side effects, stop taking the supplement and contact your health care provider. You may also want to contact the supplement manufacturer.

Take charge of your health—talk with your health care providers about any complementary health approaches you use. Together, you can make shared, well-informed decisions.

Research Funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

NCCIH supports dozens of research projects on dietary supplements and how they might affect the body.

NCCIH cosponsors the Centers for Advancing Research on Botanical and Other Natural Products (CARBON) Program. Scientists at the centers conduct laboratory research concerning the safety, effectiveness, and mechanisms of action of botanical dietary supplements that have a high potential to benefit human health.

For More Information

NCCIH Clearinghouse

The NCCIH Clearinghouse provides information on NCCIH and complementary and integrative health approaches, including publications and searches of Federal databases of scientific and medical literature. The Clearinghouse does not provide medical advice, treatment recommendations, or referrals to practitioners.

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-888-644-6226

Telecommunications relay service (TRS): 7-1-1

Website: https://www.nccih.nih.gov

Email: info@nccih.nih.gov (link sends email)

PubMed®

A service of the National Library of Medicine, PubMed® contains publication information and (in most cases) brief summaries of articles from scientific and medical journals. For guidance from NCCIH on using PubMed, see How To Find Information About Complementary Health Practices on PubMed.

Website: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS), National Institutes of Health (NIH)

ODS seeks to strengthen knowledge and understanding of dietary supplements by evaluating scientific information, supporting research, sharing research results, and educating the public. Its resources include publications (such as Dietary Supplements: What You Need To Know) and fact sheets on a variety of specific supplement ingredients and products (such as vitamin D and multivitamin/mineral supplements).

Website: https://ods.od.nih.gov

Email: ods@nih.gov (link sends email)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

The FDA oversees the safety of many products, such as foods, medicines, dietary supplements, medical devices, and cosmetics. See its webpage on Dietary Supplements.

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-888-463-6332

Website: https://www.fda.gov/

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)

Part of the FDA, CFSAN oversees the safety and labeling of supplements, foods, and cosmetics. It provides information on dietary supplements. Online resources for consumers include Tips for Dietary Supplement Users: Making Informed Decisions and Evaluating Information.

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-888-723-3366

Website: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-organization/center-food-safety-and-applied-nutrition-cfsan

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

The FTC is the Federal agency charged with protecting the public against unfair and deceptive business practices. A key area of its work is the regulation of advertising (except for prescription drugs and medical devices).

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-877-382-4357

Website: https://www.ftc.gov

MedlinePlus

To provide resources that help answer health questions, MedlinePlus (a service of the National Library of Medicine) brings together authoritative information from the National Institutes of Health as well as other Government agencies and health-related organizations.

Website: https://www.medlineplus.gov

Dietary Supplement Label Database

The Dietary Supplement Label Database—a project of the National Institutes of Health—has all the information found on labels of many brands of dietary supplements marketed in the United States. Users can compare the amount of a nutrient listed on a label with the Government’s recommended amounts.

Website: https://dsld.od.nih.gov

Key References

- Black LI, Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL. Use of complementary health approaches among children aged 4‒17 years in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2007‒2012. National health statistics reports; no 78. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

- Botanical dietary supplements. Office of Dietary Supplements website. Accessed at ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/BotanicalBackground-HealthProfessional/ on July 30, 2018.

- Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National health statistics reports; no 79. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

- Cohen PA, Maller G, DeSouza R, et al. Presence of banned drugs in dietary supplements following FDA recalls. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1691-1693.

- Crawford C, Brown LL, Costello RB, et al. Select dietary supplement ingredients for preserving and protecting the immune system in healthy individuals: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2022;14(21):4604.

- Dietary supplements. Office of Dietary Supplements website. Accessed at ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/DietarySupplements-HealthProfessional on July 30, 2018.

- Dietary supplements. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements on July 24, 2018.

- Dietary supplements: what you need to know. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/UsingDietarySupplements/ucm109760.htm on July 30, 2018.

- Dietary supplements: what you need to know. Office of Dietary Supplements website. Accessed at ods.od.nih.gov/HealthInformation/DS_WhatYouNeedToKnow.aspx on July 30, 2018.

- Geller AI, Shehab N, Weidle NJ, et al. Emergency department visits for adverse events related to dietary supplements. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(16):1531-1540.

- Gurley BJ, Fifer EK, Gardner Z. Pharmacokinetic herb-drug interactions (part 2): drug interactions involving popular botanical dietary supplements and their clinical relevance. Planta Medica. 2012;78(13):1490-1514.

- Hoofnagle JH, Navarro VJ. Drug-induced liver injury: Icelandic lessons. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1335-1336.

- Information for consumers on using dietary supplements. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/food/dietarysupplements/usingdietarysupplements on July 30, 2018.

- Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Du M, et al. Trends in dietary supplement use among US adults from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2016;316(14):1464-1474.

- Navarro VJ, Barnhart H, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Liver injury from herbals and dietary supplements in the U.S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. Hepatology. 2014;60(4):1399-1408.

- Questions and answers on dietary supplements. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/UsingDietarySupplements/ucm480069.htm on July 30, 2018.

- Stussman BJ, Black LI, Barnes PM, Clarke TC, Nahin RL. Wellness-related use of common complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2012. National health statistics reports; no 85. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2015.

Other References

- Advertising FAQ’s: a guide for small business. Federal Trade Commission website. Accessed at www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/advertising-faqs-guide-small-business on July 30, 2018.

- Ashley JT, Ward JS, Anderson CS, et al. Children’s daily exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls from dietary supplements containing fish oils. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A. 2013;30(3):506-514.

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, et al. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1419-1425.

- Bookstaver DA, Burkhalter NA, Hatzigeorgiou C. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on statin-induced myalgias. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2012;110(4):526-529.

- Brinkley TE, Lovato JF, Arnold AM, et al. Effect of ginkgo biloba on blood pressure and incidence of hypertension in elderly men and women. American Journal of Hypertension. 2010;23(5):528-533.

- Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(8):795-808.

- Cortés-Jofré M, Rueda JR, Corsini-Muñoz G, et al. Drugs for preventing lung cancer in healthy people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(10):CD002141. Accessed at http://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 25, 2018.

- Crawford C, Brown LL, Costello RB, et al. Immune supplements under the magnifying glass: an expert panel develops priorities and evidence-based recommendations for future research regarding dietary supplements. Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine. March 1, 2023. [Epub ahead of print].

- DeKosky ST, Williamson JD, Fitzpatrick AL, et al. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2253-2262.

- De-Regil LM, Peña-Rosas JP, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, et al. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(12):CD007950. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 25, 2018.

- Dietary supplement products & ingredients. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/ProductsIngredients/default.htm on July 30, 2018.

- Feucht C, Patel DR. Herbal medicines in pediatric neuropsychiatry. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2011;58(1):33-54.

- Fortman SP, Burda BU, Senger CA, et al. Vitamin and mineral supplements in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: an updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(12):824-834.

- Fransen M, Agaliotis M, Nairn L, et al. Glucosamine and chondroitin for knee osteoarthritis: a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating single and combination regimens. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2015;74(5):851-858.

- Galasko DR, Peskind E, Clark CM, et al. Antioxidants for Alzheimer disease: a randomized clinical trial with cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measures. Archives of Neurology. 2012;69(7);836-841.

- Gordon RY, Cooperman T, Obermeyer W, et al. Marked variability of monacolin levels in commercial red yeast rice products. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(19):1722-1727.

- Guidance for industry: questions and answers regarding adverse event reporting and recordkeeping for dietary supplements as required by the Dietary Supplement and Nonprescription Drug Consumer Protection Act. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/

DietarySupplements/ucm171383.htm on July 30, 2018. - Grodstein F, O’Brien J, Kang JH, et al. A randomized trial of long-term multivitamin supplementation and cognitive function in men: The Physicians’ Health Study II. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(12):806-814.

- Hemilä H, Chalker E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(1):CD000980. Accessed at http://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 30, 2018.

- Herrero-Beaumont G, Ivorra JA, del Carmen Trabado M, et al. Glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study using acetaminophen as a side comparator. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;56(2):555-567.

- Herxheimer A, Petrie KJ. Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002;(2):CD001520. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 27, 2018.

- Hochberg MC, Martel-Pelletier J, Monfort J, et al. Combined chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine for painful knee osteoarthritis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial versus celecoxib. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2016;75(1):37-44.

- Is it really ‘FDA approved?’ U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm047470.htm on July 30, 2018.

- Kahan A, Uebelhart D, De Vathaire F, et al. Long-term effects of chondroitins 4 and 6 sulfate on knee osteoarthritis: the study on osteoarthritis progression prevention, a two-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009;60(2):524-533.

- Karsch-Völk M, Barrett B, Kiefer D, et al. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;(2):CD000530. Accessed at http://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 25, 2018.

- Kenfield SA, Van Blarigan EL, DuPre N, et al. Selenium supplementation and prostate cancer mortality. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2014;107(1);360.

- Label claims for conventional foods and dietary supplements. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/ucm111447.htm on July 30, 2018.

- Kim J, Choi J, Kwon SY, et al. Association of multivitamin and mineral supplementation and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2018;11(7);e004224.

- Liira J, Verbeek JH, Costa G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for sleepiness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;(8):CD009776. Accessed at http://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 30, 2018.

- Liu ZL, Xie LZ, Zhu J, et al. Herbal medicines for fatty liver diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(8):CD009059. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 25, 2018.

- Macpherson H, Pipingas A, Pase MP. Multivitamin-multimineral supplementation and mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013;97(2):437-444.

- Masada-Atsumi S, Kumeta Y, Takahashi Y, et al. Evaluation of the botanical origin of black cohosh products by genetic and chemical analyses. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2014;37(3):454-460.

- Moyer VA. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplements for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(8):558-564.

- Navarro VJ, Seeff LB. Liver injury induced by herbal complementary and alternative medicine. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2013;17(4):715-735.

- New dietary ingredients in dietary supplements—background for industry. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed at www.fda.gov/Food/DietarySupplements/ucm109764.htm on July 30, 2018.

- NIH centers for advancing research on botanical and other natural products (CARBON) program. Office of Dietary Supplements website. Accessed at ods.od.nih.gov/Research/Dietary_Supplement_Research_Centers.aspx on July 30, 2018.

- Office of Inspector General. Dietary Supplements: Structure/Function Claims Fail To Meet Federal Requirements. Office of Inspector General website. Accessed at https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-11-00210.asp on July 25, 2018.

- Pavelká K, Gatterová J, Olejarová M, et al. Glucosamine sulfate use and delay of progression of knee osteoarthritis: a 3-year, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(18):2113-2123.

- Pawar RS, Grundel E, Fardin-Kia AR, et al. Determination of selected biogenic amines in Acacia rigidula plant materials and dietary supplements using LC-MS/MS methods. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2014;88:457-466.

- Reginster JY, Deroisy R, Rovati LC, et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9252):251-256.

- Sawitzke AD, Shi H, Finco MF, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of glucosamine, chondroitin sulphate, their combination, celecoxib or placebo taken to treat osteoarthritis of the knee: 2-year results from GAIT. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2010;69(8):1459-1464.

- Seeff LB, Bonkovsky HL, Navarro VJ, et al. Herbal products and the liver: a review of adverse effects and mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):517-532.

- Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(1):CD005614. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com on July 25, 2018.

- Snitz BE, O’Meara ES, Carlson MC, et al. Ginkgo biloba for preventing cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA. 2009;302(24);2663-2670.

- Song Y, Xu Q, Park Y, et al. Multivitamins, individual vitamin and mineral supplements, and risk of diabetes among older U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):108-114.

- Tainted products marketed as dietary supplements_CDER. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed at www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/sda/sdNavigation.cfm?sd=tainted_supplements_cder&displayAll=false&page=6 on July 30, 2018.

- Wallace ED, Oberlies NH, Cech NB, et al. Detection of adulteration in Hydrastis canadensis (goldenseal) dietary supplements via untargeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2018;120:439-447.

Acknowledgments

NCCIH thanks D. Craig Hopp, Ph.D., and David Shurtleff, Ph.D., NCCIH, for their review of the 2019 update of this publication.

This publication is not copyrighted and is in the public domain. Duplication is encouraged.

NCCIH has provided this material for your information. It is not intended to substitute for the medical expertise and advice of your health care provider(s). We encourage you to discuss any decisions about treatment or care with your health care provider. The mention of any product, service, or therapy is not an endorsement by NCCIH.